Flash attention

What is flash attention?

The attention mechanism is a key component of transformer architectures, which have significantly advanced the field of AI. However, the practical implementation of attention mechanisms is often limited by GPU memory I/O speed rather than GPU compute power. Flash Attention addresses this memory bottleneck, accelerating the training speed of transformer models by up to threefold. Additionally, it enables the use of longer context windows, which are also constrained by memory limitations. It was proposed by Tri Dao et al. in 2022 in this paper.

Compute-bound, memory-bound and overhead

Most software people (which includes the majority of ml engineers) do not really understand hardware. We tend to think of codes as logical blocks and ignore the practical implications of what we write. For example, we often ignore how GPU needs to first load data to memory before performing computation, and if we can’t load the data fast enough, we can have all the compute powers in the world and it wouldn’t make a difference in training speed. Here is a good post by Horace He on this topic, where he explained all the components that leads to time expenditure: compute, memory and overhead. Generally, matrix multiplication is compute-bound while element-wise operations such as matrix additions are memory-bound in modern GPUs.

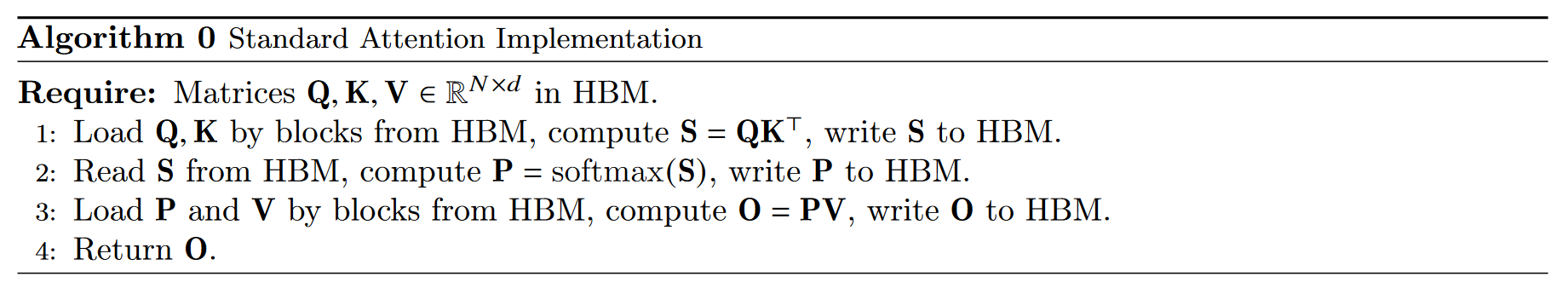

In attention mechanism, we have the following:

\[\begin{aligned} S &= QK^T \\ O &= mask(softmax(dropout(SV))) \end{aligned}\]where $Q, K, V$ are the query, key and value matrices respectively, $S$ is the attention weights, and $O$ is the final outputs. $mask$ (optional), $softmax$, and $dropout$ (optional) are all element-wise operations. What we typically do in terms of memory is as follow:

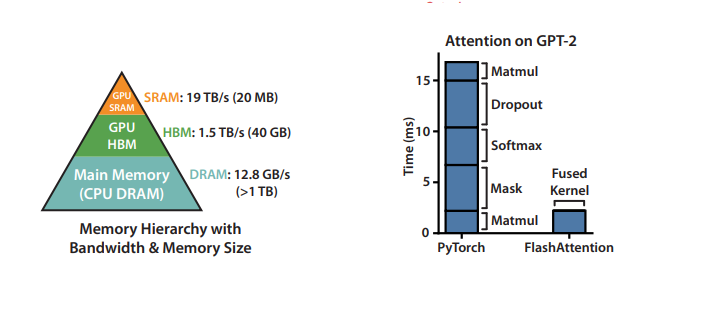

where HBM stands for high bandwidth memory, which is the slower GPU memory in terms of I/O speed as opposed to SRAM (static random-access memory), its faster counterpart. As we can see, we are loading and off-loading to HBM repeatedly, and it is the source of our memory bottleneck. What if we can better utilize our hardware memory, especially the faster SRAM? Below are figures from the paper highlighting this idea:

On the left, we can see that we have a pyramid structure for memory, where the faster the memory I/O, the less its size. On the right, we have the conventional attention mechanism profiling, where the bulk of time is spent on memory-bound operations. The fused kernel is after we fully utilise the SRAM memory as will be explained below.

Tiling and softmax

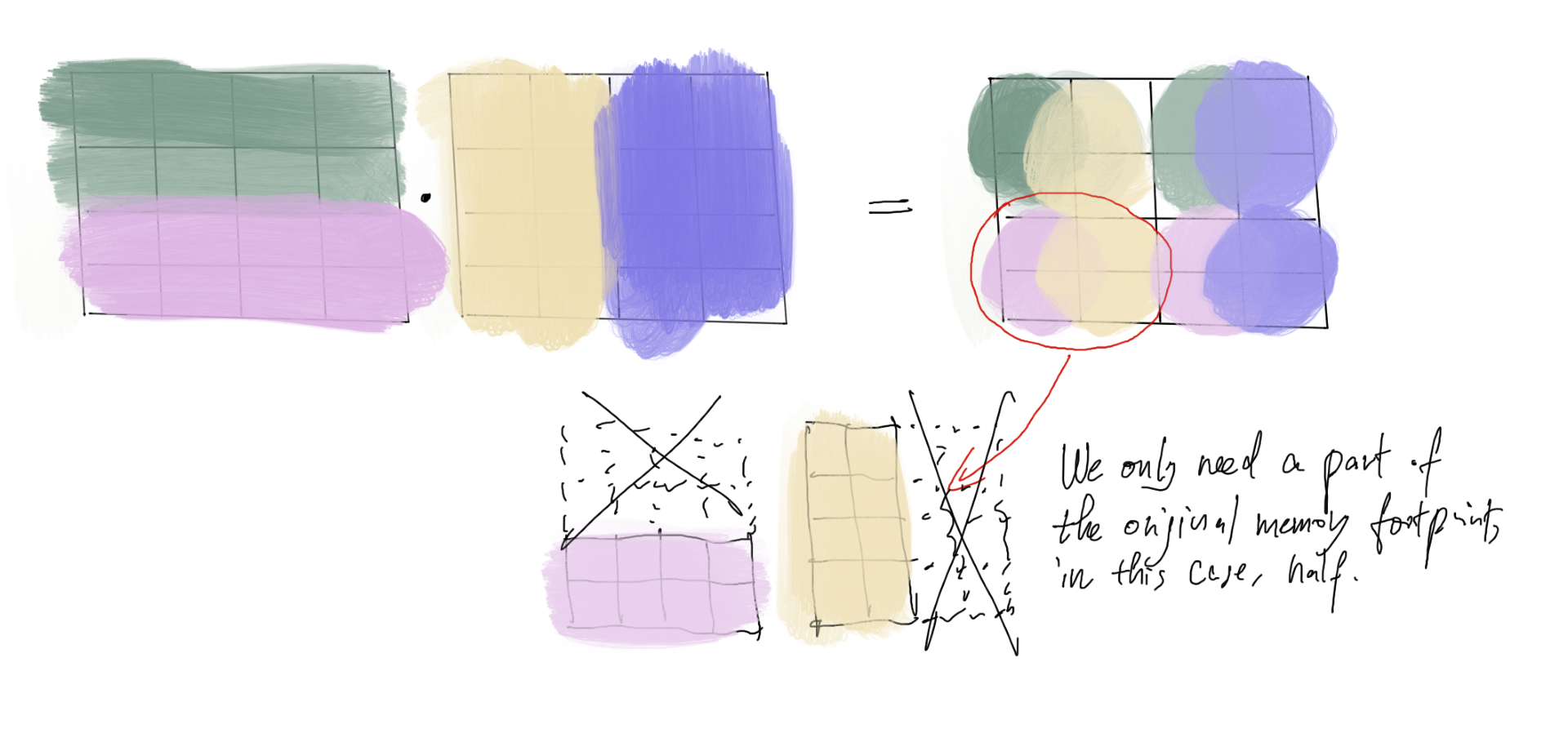

The first question one might ask is how come we only use HBM and not the faster SRAM? Well it is because we don’t have a large enough SRAM to fit all the necessary data (hence the memory bottleneck). A typical context window can go up to 8k in length, which corresponds to the $N$ dimension of the $N$ by $d$ matrices $K$, $Q$, $V$, where $d$ is the embedding dimension. Taking a typical $d = 512$, we have \(8000 \times 512 \times 4(\text{assuming 4 bytes floating point precision}) \times 3 (\text{3 matrices}) \approx \text{50MB}\), which quickly fills up the 20MB memory of SRAM. Luckily, as we know from linear algebra, matrix multiplications have property that allows the computation to be performed in blocks as shown in the next figure:

here, we used the multiplication of two 4 by 4 matrices as an example (in flash attention the matrices will be $N$ by $d$ and $d$ by $N$), but the main idea is that the resulting matrix can be divided into non-overlapping blocks, where the computation of each block only needs a subset of the original input. This idea is called tiling and constitutes the main idea of the flash attention paper. In fact, a small enough tiling allows us to only load parts of the rows and columns of $Q$ and $K^T$, bypassing the high memory usage caused by the large $N$.

One obstacle remains: the softmax operation. As shown above, to get to the final outputs $O$, we have to go through 2 matrix multiplications ($S = QK^T$ and $SV$), one dropout operation, one softmax operation and one masking operation. The matrix multiplications can be solved by tiling, the dropout and the masking operations can both be done locally within the tiling area without needing out of tile inputs, but the softmax function ($\sigma$) needs the results of the entire row (including out of tile inputs) as it has the following formulation:

\[\begin{aligned} \sigma(z)_i = \frac{e^{z_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^K e^{z_j}} \end{aligned}\]here, $z$ represents the input vector to softmax (in our case, the rows of $SV$), $K$ is the length of $z$. If we want to effectively reduce memory footprint with a small tile, we can see that the denominator will need the results across many tiles. Luckily, softmax can be written in an equivalent form that allows us to bypass this obstacle, detailed in a 2018 paper by NVIDIA. First, for numerical stability, we can normalize the entries of the input $z$ by substracting the vector’s maximum value as so:

\[\begin{aligned} \sigma(z)_i = \frac{e^{z_i}}{\sum_{j=1}^K e^{z_j}} = \frac{e^{z_i - max(z)}}{\sum_{j=1}^K e^{z_j - max(z)}} \end{aligned}\]where $max(z)$ signifies the maximum value among all the entries \(z_{i (1 \le i \le K)}\) of $z$. Second (this is the core idea), let $d_i$ be the first $i$ terms of the denominator, we can extract the following recurrence relation which allows us to break the calculation of softmax into parts:

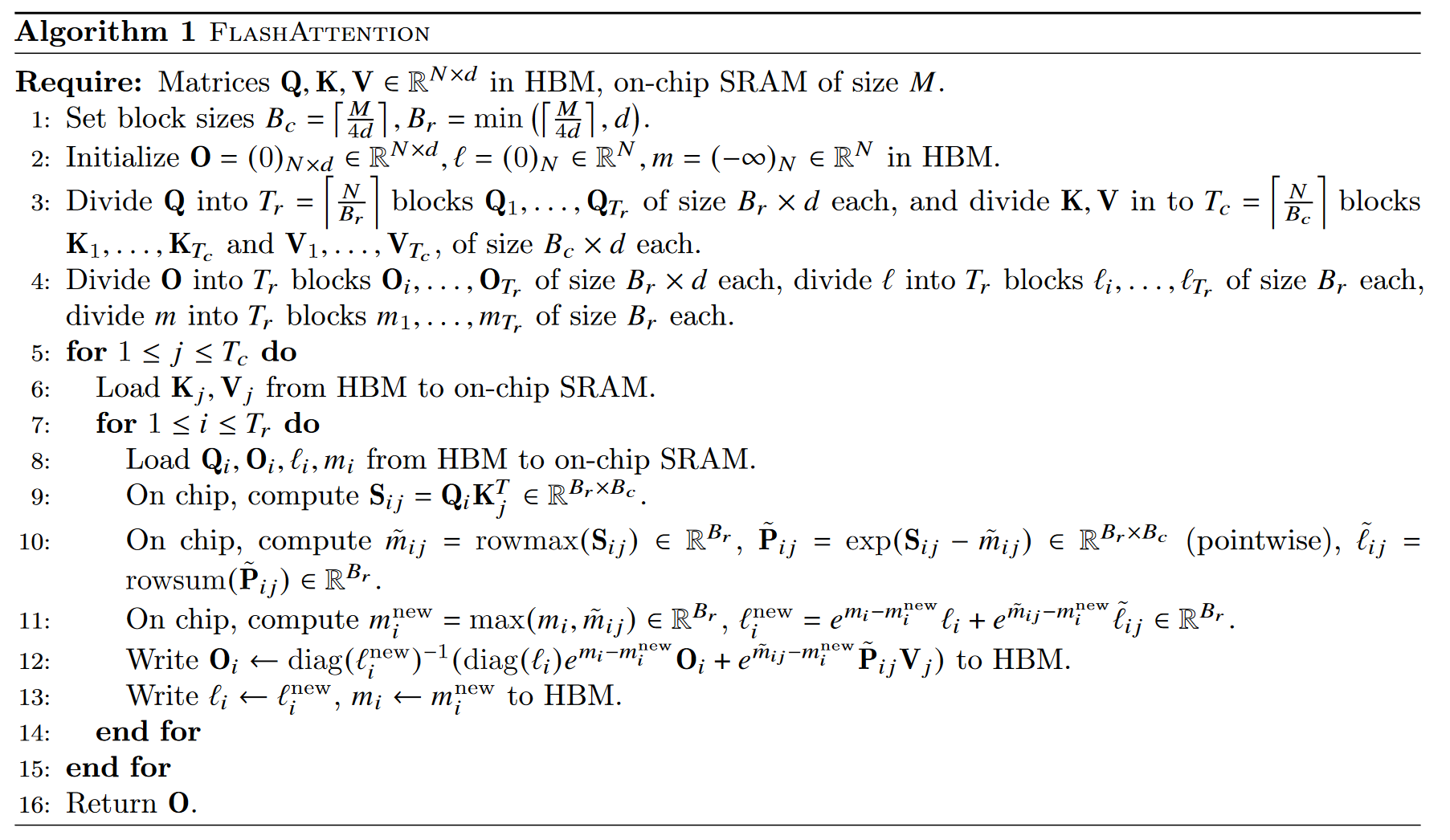

\[\begin{aligned} d_i &= \sum_{j=1}^i e^{z_j - max_i(z)} \\ &= \sum_{j=1}^{i-1} e^{z_j - max_i(z)} + e^{z_i - max_i(z)} \\ &= (\sum_{j=1}^{i-1} e^{z_j - max_{i-1}(z)})e^{max_{i-1}(z) - max_i(z)} + e^{z_i-max_i(z)} \\ &= d_{i-1} e^{max_{i-1}(z)-max_i(z)} + e^{z_i - max_i(z)} & \text{relative to previous step}\\ &= (d_{i-2}e^{max_{i-2}(z) - max_{i-1}(z)} + e^{z_{i-1}-max_{i-1}(z)})e^{max_{i-1}(z)-max_i(z)} + e^{z_i-max_i(z)}\\ &= d_{i-2}e^{max_{i-2}(z)-\cancel{max_{i-1}(z)}+\cancel{max_{i-1}(z)}-max_i(z)} + e^{z_{i-1}-\cancel{max_{i-1}(z)}+\cancel{max_{i-1}(z)}-max_i(z)} + e^{z_i-max_i(z)}\\ &= d_{i-2}e^{max_{i-2}(z)-max_i(z)} + e^{z_{i-1}-max_i(z)} + e^{z_i-max_i(z)}\\ &= ... \\ &= d_{i-n}e^{max_{i-n}(z)-max_i(z)} + \sum_{k=0}^ne^{z_{i-k}-max_i(z)} & \text{relative to the $n_{th}$ previous step ($n$ can be tile size)} \end{aligned}\]where $max_i(z)$ signifies the maximum value among the first $i$ entries of $z$. This relationship is significant because if we divide the input $z$ (or rows of $SV$) of softmax into parts and compute step by step within the tiles, we can use the result of previous tiles to gradually approximate the final softmax of the whole row, until we finally reach the exact softmax at the last tile. This leads us to the new flash attention formulation, where we can effectively perform tiling with softmax:

notice how line 11 of the algorithm corresponds to exactly the last line of the derivation above, where $m_i^{new}$ corresponds to $max_i(z)$ and $l_i^{new}$ corresponds to $d_i$1. Line 12 then calculates the updated softmax for the tile in a matrix form, where $diag(l_i^{new})^{-1}$ serves to update the softmax’ denominator in a new tile, while $O_i + \tilde{P}_{ij}V_j$ update the nominator2.

The algorithm follows a similar idea in backpropagation, where instead of using the typical $O(N^2)$ memory matrix of attention weights, it stores the intermediate $O(N)$ memory softmax normalization statistics (line 13 of algorithm above) in the forward pass, and uses them to recompute the attention weights with $Q$, $K$, $V$ in the backward pass. The details can be found in Appendix B of the original paper.

Implementation

As Pytorch does not allow direct GPU memory manipulation, the algorithm is implemented in NVIDIA CUDA, and is a complete beast of a code base which I have no interest in spending more time digging. For most everyday uses, starting from Pytorch2.0 flash attention is incorporated into the api call scaled_dot_product_attention. However unlike normal attention, the returning of attention weights (intermediate matrix $S$) is currently unsupported. Since the release of the paper, most big companies have adopted flash attention to train their models in a short period of time. As attention mechanism has been studied and optimized so much as the backbone of modern AI, this paper marks the possibility that some single researcher can still somehow beat the billion dollars industry just by a clever algorithmic trick.

-

There’s an important detail here: notice how \(\tilde{l}_{ij}\) corresponding to $\sum_{k=0}^ne^{z_{i-k}-max_i(z)}$ is adjusted by a factor of $e^{m_{ij} - m_i^{new}}$, this is to account for the fact that the maximum can increase relative to what is being used in previous calculations. ↩

-

Again, the factors $e^{m_i-m_i^{new}}$ and \(e^{\tilde{m}_{ij}-m_i^{new}}\) are to account for the potentially changing maximum. ↩